After three years, we have turned the page on a young game series called Life is Strange. On March 6 2018, Life is Strange: Before the Storm (BtS) released its last episode, aptly titled “Farewell.” Though the original developer of the series, Dontnod, has plans for what is currently only known as Life is Strange Season 2, if early news is to be believed, “Farewell” marks the end of the series’ time with protagonists Max Caulfield and Chloe Price and the world of Arcadia Bay.

Farewell, indeed.

The Life is Strange series up to this point has developed a surprisingly large and dedicated fanbase. Even before BtS, the original game Life is Strange (LiS) spawned a lively and supportive community, a not insignificant part of which focused on helping players through “post LiS depression,” a term fans used to describe the mixed feelings of loss, empathy, and sadness from finishing the game. A slew of critical awards accompanied its release and, at the time of this writing, Steam player reviews rate both games as “overwhelmingly positive” from over 100,000 reviews (96% and 94% for LiS and BtS respectively at the time of this writing), among the highest on the platform. According to Dontnod, over 3 million copies have been sold of the original game. Not bad for an indie game about some teenage girls in a stereotypically “bro-ey” medium.

By all of these accounts, LiS has been a success. But when you start to ask the question, “why?” you’ll be forgiven for drawing a lot of blanks. The LiS series doesn’t seem, on-paper at least, to warrant this level of success.

In spite of its failings as a choice/consequence based game, and in some ways because of those failings, the two games of Life is Strange are some of the most important games of this generation because of their exceptional way of connecting its characters and world to players.

Oh yeah, FULL SPOILERS BELOW (duh).

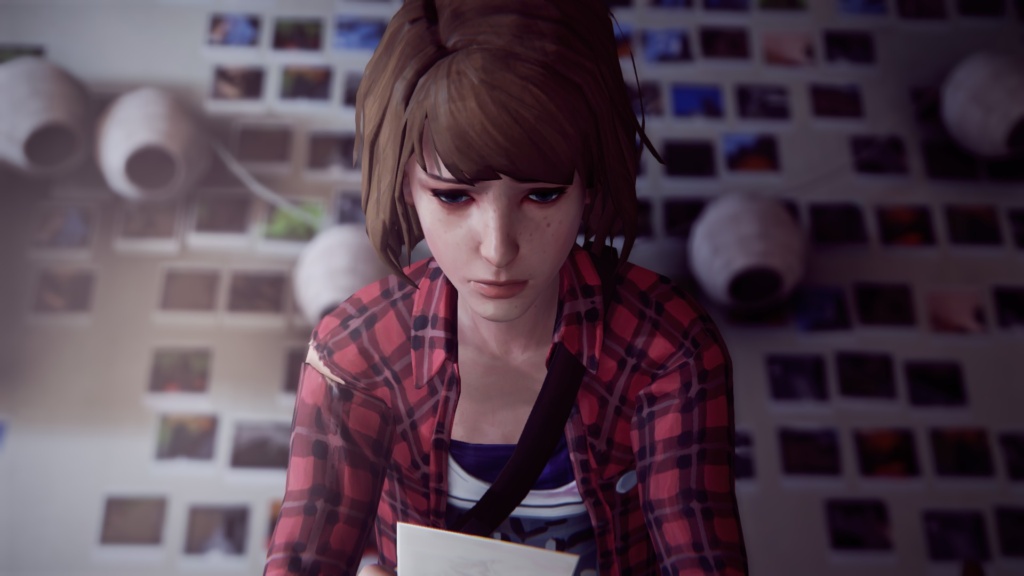

If you haven’t already, I’d highly recommend you play at least one of the LiS games but here’s enough to get you up to speed. The 5-episodes of the original Life is Strange game is a choice/consequence, episodic adventure game that puts players in the head of Max Caulfield, a senior photography student recently returned to her childhood home, the small Oregon coast town of Arcadia Bay. After a vision of an impending storm that wipes out the town, Max discovers she has time-traveling powers, allowing her to reverse time and even bend realities. After reuniting with her childhood best friend, Chloe Price, Max and Chloe embark on a mystery adventure to understand the apparent doom of the town and find a missing girl, Rachel Amber, who seems to be at the heart of a darker mystery in town. Life is Strange: Before the Storm serves as a prequel. Set two years before the original game, the three episodes of BtS explores Chloe’s past and her unique relationship with Rachel before Rachel’s disappearance immediately prior to the original game.

Let’s first take a closer look at why this series shouldn’t be make the grade.

“The [game] where everything is made up and the [choices] don’t matter”

To start off, the Life is Strange series fails as part of the choice/consequence genre. It simply doesn’t have meaningful choices in the way that the genre has been defined in recent years. Choice-based games are generally critiqued, by critics and fans alike, for the impact of player decisions on the story, characters, and gameplay. The point of the genre is to make meaningful changes in the game rooted in player decisions over the course of the game, molding the experience to the player and responding uniquely to their choices. Admittedly, it’s a high bar and an ambiguous one at that. So to start talking about this, let’s actually look at the end.

Where else can a player make a more meaningful decision than the way the game ends? The genre itself takes a huge nod from Choose Your Own Adventure books in which the entire point is practically to customize your own ending to a story. The entire 5 episodes of LiS builds up to a single final decision which rather bluntly overwrites all of the choices built up in the player’s decision-making thus far: choose to save Chloe or save Arcadia Bay. No matter which way you choose, the story wipes out the world that the player affected in their decisions. If you save Chloe, the entire town of Arcadia Bay is destroyed, rendering your choices with its characters and the town itself (literally) in shambles. Alternatively, if you save Arcadia Bay, the game puts you back in time to the beginning of the game literally to re-write the past in a cutscene so that the story you just played for 5 episodes didn’t happen. As you’d imagine, the game got a lot of flack for this ending. Just as a comparison to understand how this has “gone down” in the past, let me give you an example of another choice-heavy game that got a lot of flack for its overly simplistic ending choices.

Mass Effect 3 (ME3), the finale of an ambitious and critically acclaimed 3-part sci-fi RPG, set a dangerous precedent for decision-games. Yes, there is a reason why I mention a AAA sci-fi opera like Mass Effect in a discussion about Life is Strange, so bear with me. Arguably the most unique and significant part of the Mass Effect series was the concept of stringing decisions across games; a decision in Mass Effect 1 could have unforeseen consequences in later games. ME3 was the supposed culmination of those collective decisions in a grand finale to cap off this epic adventure. To put it lightly, it didn’t turn out like that. ME3 famously got plenty of criticism for its final three-choice Red/Green/Blue decision that determined the entire ending. It was controversial to say the least (e.g. Bioware received 400 red, green, and blue cupcakes as part of an oddly assembled protest). Discussions erupted from players and media alike about the philosophical debate of games as art vs a product beholden to its customers, the toxicity of gaming communities, and the over-promising of developers, among others. Long story short though, the situation was serious enough that Bioware went back to re-make some of the ending sequences and even added an additional choice based off of this uproar. The damage was done however and the cookie-cutter “RGB” ending remains, justly or not, a huge part of ME3’s, and arguably Bioware’s, lasting legacy. This debacle served as a warning to future choice-driven games: if you’re going to tout player decisions, you better follow through.

Now here is where we come back to Life is Strange. Though obviously not a AAA title with a similarly huge fanbase, LiS, a choice-based game I remind you, pulls a similar sin to that of ME3. The entire ending was determined by a single decision with only two options; in this regard, LiS actually has even fewer options than ME3 offered. But LiS still fares better than BtS. Where LiS had an ending in which the player could influence its characters in a meaningful way, BtS didn’t even have that.

BtS, for all its merits as a more polished version of the LiS framework, is nonetheless fundamentally rooted in a way that destroys player decision-making: it’s a prequel. For LiS fans, they all already know how the story of Chloe and Rachel plays out. Though the ins and outs of their relationship was never seen in LiS (but still heavily alluded to) players already knew that Chloe and Rachel would create a unique, strong relationship that would tragically be torn apart. No matter your decisions, Chloe would always develop into the same Chloe that you encounter in LiS. The same can be said of Rachel. Additionally, players already knew how the rest of the main returning characters, like Joyce, David, Principal Wells, Nathan, and Victoria, would end up. The bonus episode, Farewell, is similar. It’s the decisive moment of Max and Chloe’s stories, the one moment that reverberates through their respective arcs across the entire series…but players already knew what was going to happen. Max would leave for Seattle, Chloe’s father would die in a car crash, and Chloe would develop her teenage rebellion identity to cope with both losses.

To be clear, there is nothing wrong with these stories and these characters because the endings are known and the choices made in the games don’t shape different endings on player choices. There’s something to be said about watching a story you know the ending to, but don’t know the exact strokes that led there. Hell, we all knew the ending of Star Wars Episode III when it came out and we all knew Titanic was not going to make it to harbor before we even got our popcorn ready. Indeed, much of the power behind BtS was knowing the ultimate destiny of Chloe and Rachel. But the fact of the matter is that LiS as a series fails as a choice-based pair of games because even after 9 episodes, the player only gets one decision that changes anything: sacrifice Chloe or Arcadia Bay.

To Stand Out In the Crowd

On top of its failure as a choice-based game, LiS as a series lacks a core gameplay identity. Most games accomplish this with unique gameplay mechanics. The game part of the game (generally speaking). Most series have a bread-and-butter game mechanic (or several) that serve to set that series apart from others but also maintain continuity across iterations. Telltale has their sometimes-dreaded character influence mechanism (“they will remember that”), Bioware has their dialogue wheel, Portal has its distinct 2-way portal puzzling etc. Now, this is not to say that every game needs a standout mechanic, however big or small, but even minor distinguishable mechanics or setups help them stand out from the crowd. And for a series, these kinds of things help keep continuity between games. The holy trinity of gun-grenade-melee is part of what makes each Halo iteration Halo, the tiled map and pawn-like units make each Civilization game feel like Civilization, etc. To be sure, not a necessary, component but again one that helps games stand out as themselves and not others. Unfortunately, LiS, doesn’t have much luck here either.

With the news that LiS as a series is moving away from its current setting and characters, you’d be forgiven for wondering what else makes the game standout as uniquely LiS. The original game had time-warping powers, a clever twist to the decision-game genre. BtS however, replaced that mechanic with Chloe’s ‘Backtalk’ feature and, though the mechanic was fun, it didn’t define the game in the same way as Max’s powers. Max’s powers were a significant, ever-present part of the way players interacted with the world, characters, and even the story. As a Max-centered mechanic, it didn’t make sense to continue it in the Chloe-centered BtS. In contrast, Chloe’s backtalk feature only appeared a handful of times per episode. Farewell (for chronological reasons) doesn’t have either! But still, the Life is Strange series manages to surprise us by still standing on its two feet, after all of this criticism (remember those extremely high player ratings?). If anything, the success of BtS and Farewell shows how Life is Strange, as a series, is not defined by a core gameplay mechanic.

And here we reach the crux of this whole matter: Life is Strange manages to stay relevant, and I think gloriously so, even when you’d think it shouldn’t. I’ll tell you right now that it’s not the necessarily the story that keeps it afloat; LiS had tons of plot holes and its overall story bordered on ludicrous sometimes (and not in an Inception-appreciated kind of ludicrous). The game is pretty, but it’s not stand-out gorgeous, at least in comparison to the big AAA games. The artistic and musical style is bold and charismatic but there are a lot of indie games that can say similarly. There is no ‘mastery’ goal in it that drives you to further challenges—you cannot ‘master’ or ‘get good’ at these LiS games. Though the voice work of its main cast was great, the scripts could lean into campy and uninspired territory pretty quickly, particularly for minor characters. The animations, for the first game especially, were stiff and the lip-dubbing noticeably under-developed. And bluntly, it’s a sad, disturbing, heart-wrenching set of games. To be clear, these games get dark. Counter to what much of the gaming industry is focused on, i.e. evoking positive emotions (video games are supposed to be fun, right?!), these games double down on the depressing side of life. Calling these games “fun” just… doesn’t quite fit. The Life is Strange series does none of these things “right,” by many typical standards. Instead, Life is Strange brings two big areas to the forefront; two areas that, in the absence of everything else, stand out as all the more important: emotional connection to characters.

Characters First and Foremost

Game characters have always had pull on us players. It is no wonder that modern games are adapting to capitalize on this character-heavy approach. Blizzard has put substantial effort to establish the characters of Overwatch. They even have a set of—damn impressive I might add—animated shorts to further develop their characters and get players to engage with them as characters and not just classes or avatars. Rainbow Six: Siege has made a similar effort to constantly expand their roster of operators, taking great pains to distinguish each one. And these are multiplayer shooters! Hell, DOTA and League of Legends have legendarily (pun intended) huge rosters and are doing the same thing. And single-player games, the go-to domain for this kind of character-establishing labor, have been making engaging characters for a while now. This is Ellie and Joel in The Last of Us. This is about seeing out Nathan Drake and his band of adventurers in Uncharted. This is about Final Fantasy VII (it came out 15+ years ago and that scene is still one of gaming’s most defining moments). This is Clementine from The Walking Dead. This is Shepard and the Normandy crew from Mass Effect. But where those games had something else to rely on— breathtaking graphics and a compelling narrative, off the walls adventure mixed with a dose of self-conscious humor, the 7th iteration in a standard-setting JRPG franchise, etc.— the Life is Strange series goes all in for the believability, relatability, and relationship players make with Max and Chloe.

Above all else, the Life is Strange series is about its characters. Max and Chloe are the at the heart of what the series has to offer. They are the relatable, imperfect, and evocative characters that serve as our eyes and ears to the world. The series is unafraid of bringing you along for the ride and showing exactly how and why they have become who they are and give you an unfiltered view into their changes across their respective games. Indeed, the series depicts the tragedy of their story from beginning to middle to end. The characters are the stars of the show here and they drive the game towards something greater than the sum of its inconsistent parts. Part of this can be seen in the thematic interplay between the protagonists and the player.

The series puts the player into an exclusive relationship with the protagonists, one that supports the major themes. Take Max for example. She is the vehicle-of-knowing for the player in the original game; players know the world through her eyes and ears, knowing her perspective on the world. Max, just like you at the beginning of the game, is new to the workings of Arcadia Bay having spent the past several years in Seattle. The game slowly reveals her past in Arcadia Bay, but a good portion of the game is acquainting herself (and by extension, the player) to the people and world of Arcadia Bay. And since Max’s story is about the mysterious twists of time and the “WTF”-ness of her powers, butterfly effects, and the ever-darkening mystery she falls into, we as the player are the only ones who truly understand her plight. If you choose to sacrifice Chloe, Max goes back in time to re-write the events of their shared experience and we players are left as the only ones who understand the mindfuck of a week she endured across the game; we are Max’s only confidant. And if you choose to sacrifice Arcadia Bay, you are the only one besides Max who understands what it’s like to give up everything for the closest person in your life; even Chloe doesn’t understand exactly what Max went through and the weight of making that final decision and all of the decisions leading up to it. Nobody understands Max’s experience—that is except for us, the players. Truly, we are Max’s “partner in time.”

And partners through tough times as well. The series explores some really mature themes. And no, not the “violence/gore” or “sexual themes” you’ll see on the ESRB ratings of many other M rated games. No, the Life is Strange series includes a serial killer that drugs and murders teenage girls, frank depictions of suicide, depression and cyber-bullying, and date-rape drugs, all the while exploring overarching themes of grief, sacrifice, and the end of childhood. Max and Chloe not only open our eyes to these heavy topics, they endure immense, unfiltered pain right in front of us, and in some ways, along with us; I think Ashley Reed of Gamesradar hits the nail on the head in her review;

“[Life is Strange] takes risks, talking about the transition into adulthood in a frank way that games struggle to pull off, if they try at all. And in putting its characters out there at their most vulnerable, it hits a nerve that’ll still sting hours, days, weeks after you turn the game off.”

It’s heavy stuff, and though not always gracefully handled, that a series even directly tackles such topics so well at all is exceptional. It’s stuff that is not typically covered in this medium. Only recently have video games really expanded to these kinds of serious topics in serious ways: Hellblade: Senua’s Sacrifice in its handling of mental illness, Undertale’s trippy meta-examination of morality, and whatever the hell is up with Limbo and Inside, being some prime recent examples. It’s exciting to see video games becoming more than just entertaining but also to be moving.

The Connection and the Way Forward

The Life is Strange series’ shortcomings as games make its player/character relationship all the more distinctive and important to the future of games. Life is Strange is certainly not the first to start this character-focused trend—like I mentioned, games have had engaging and impactful characters and stories for a while now—but the Life is Strange series embodies the essence of this trend. Intentional or not, Life is Strange put all its eggs into one basket, forgoing the common game elements of its genre and hinging itself upon its characters and their connection to players. Not only that, Life is Strange takes a huge risk in connecting to players through a mature, emotionally-heavy experience. Its successes in this regard show not only that player/character relationships matter, but that they matter a lot— enough to salvage an otherwise average game and lift it into something salient, immersive, and moving. And ‘moving’ is where we are heading. The Life is Strange series shows us that games can be more than just fun—that they can do more than entertain us—games can also move us: to be reflective, to look at the world differently, to connect with ourselves and others.

When I look at the gaming industry, I’m excited to see how this ‘connection’ and ‘relationship’ aspect is becoming more apparent in video games. We are seeing more and more games taking on new relationships and interesting protagonists that are full of nuance and relatability, and stories that speak to players the world over. Video game developers are pushing more remasters of old titles (a la Crash Bandicoot, recently announced Spyro, The Shadow of the Colossus, Uncharted: the Nathan Drake Collection, Halo: The Master Chief Collection etc.) which, no matter your opinion on whether remasters are a good or bad trend, tells us that the power of nostalgia—the connection players have with characters, stories, and worlds curated over years of playing—matters in a big way. Outside of the games themselves, we are also seeing a renaissance of video game culture. People are playing video games now more than ever. And current gamers are becoming more prominent with the development of esports, conventions full of thousands of fans and cosplayers, and the ever-increasing connect-ability of online play. Video game streamers on Twitch and YouTube Let’s Play’s are connecting fans of online personalities and game-lovers alike. There is a lot to be excited about in modern gaming. The Life is Strange series is certainly not the first to start this connection and relationship-centric approach, but it showed in the absence of the rest of many “game-y” things that define this kind of game, how important it was; just raw connection. As 9-game chapters stripped of its usual genre-defining features, instead pushing relationships between player and character, Life is Strange shows us that relationships and connection are vital to the future of gaming. If that is not a triumph, I don’t know what is.

As we look towards a future of greater connectivity and ever more engaging stories, characters, and worlds in video games, the lessons learned from Life is Strange will become all the more important. Maya Angelou once said, “I’ve learned that people will forget what you said, people will forget what you did, but people will never forget how you made them feel.” Life is Strange is a perfect example of what games can be–a powerful medium for meaningful experiences that help us feel more connected to each other and even our own selves. So while the 9-episodes of Life is Strange may not jump out as an obvious inclusion in the list of “most important games of the generation,” all of modern gaming owes a debt to Max and Chloe and Life is Strange.

“We’re always together, okay? Even when we’re apart. We’re still Max and Chloe.

I will always, always love you.

Goodbye.“