Over the past decade, online data has become deeper and more prevalent than ever. We’ve shifted towards online services and systems, and users–just normal people like you and me–have become the main creators of internet content in the “Web 2.0.” As a result we now know exponentially more about people on the internet than ever before. Tweets, Facebook shares, and Instagram photos are everywhere and ingrained into people’s daily life (Gosling, Augustine, Vazire, Holtzman, Gaddis, 2011). Researchers from universities and web giants have turned their respective skills to this informative, lucrative, and increasingly relevant online space. They have developed new techniques to make sense of the waves of information flowing into, and out of, the digital world. A new direction in this area is extracting users’ personality from their online data. Both the academy and digital industry care about this area, but they have increasingly butted heads over, essentially, one big question–how the heck do you ethically study people online?

What is Personality and Why Does It Matter Online?

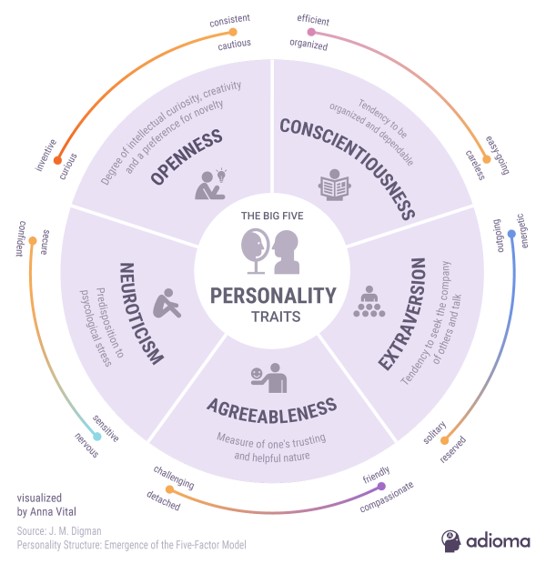

Online personality research itself is a bit opaque, so let’s start with the base. When I say “personality”, I (and most psychologists) refer to the Five Factor Model of personality (McCrae & Costa, 1987). The most widely known and robust model to date, the “Big-5” describes five traits that make up personality: Openness to experience, Conscientiousness, Extraversion, Agreeableness, and Neuroticism. Your personality is your particular spread across each of these five dimensions that is relatively consistent over time.

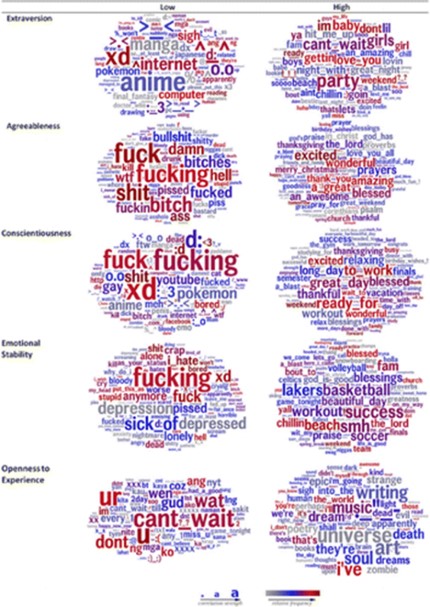

You typically evaluate personality in two main ways—direct or indirect measurement. Direct measurement basically means asking people questions. Up front, your classic “hey, this is a personality quiz! Circle the statements that apply to you” kind of stuff. Though a somewhat blunt and obvious method, it’s the main way personality has been studied for decades (McCrae & John, 1992). Heck, it’s the way most things are studied in psychology in part because it’s really easy, especially online. Alternatively, indirect measurement is a newer, fancier way to measure personality. The idea is to use a combination of algorithms, AI, and machine-learning to determine personality through general online data—intuiting users’ personality traits from their presence online. Though most current research has focused on analyzing language from tweets, blogs, and video transcripts (Farnadi et al., 2016), we’ll eventually start measuring personality from people’s usage of online images, audio, and mobile sensors (Boyd & Pennebaker, 2017). Though technically challenging, this indirect way has opened up previously inaccessible wells of data that may be more revealing and nuanced than ever.

But why go through all this effort to measure personality online at all? Because, online personality offers a tantalizing opportunity to understand a fundamental aspect of psychology of billions of users—e.g. what they do, buy, and what kinds of content that certain personalities engage with relative to others. Indeed, one of the great successes of the Five Factor Model was how easy it was to use all over the place (McCrae & Costa, 1990). For academic researchers, online personality research offers a huge new universe to understand personality, using data that’s far closer to the real-world people live in (Boyd & Pennebaker, 2017; Wrzus & Mehl, 2015). No need to bring people into a lab, you can study them in the wild! They’ve found, for example, that people fairly accurately bring their offline personalities online (Gosling, Augustine, Vazire, Holtzman, Gaddis, 2011). One’s personality online is not more or less ‘true’ than one’s offline personality (Marriott & Buchanan, 2014). In other words, while you might not be the ‘same’ online as you are offline, your underlying personality goes with you both places.

Alternatively, business researchers are trying to enhance their products and services. The general idea is that you first determine users’ personality, then track what they do online to see if different traits are more associated with certain systems, products, and content than other personalities (Kosinski, Bachrach, Kohli, Stillwell, & Graepel, 2014; Souiden, Chtourou, & Korai, 2017; Han-Chung et al., 2018). In other words, can you tailor products and services via personality? Make a social chat app more agreeable for introverts? Maybe more nihilistic people are less likely to click on certain popup ads?

Remember, personality is relatively stable over time (McCrae & Costa, 1990). So, if you can understand users’ personality (and what those personalities end up doing) you then have deep, pretty reliable information about how to tailor content for, and maximize profit from, users. But you might already see the writing on the wall here. While not bad in and of themselves, these kinds of business aims are very different from those of the academy. While both are trying to study the same thing at the same time, their diverging perspectives and baggage have made a confusing research space where ethical boundaries have become stretched and blurred.

The Flashpoint

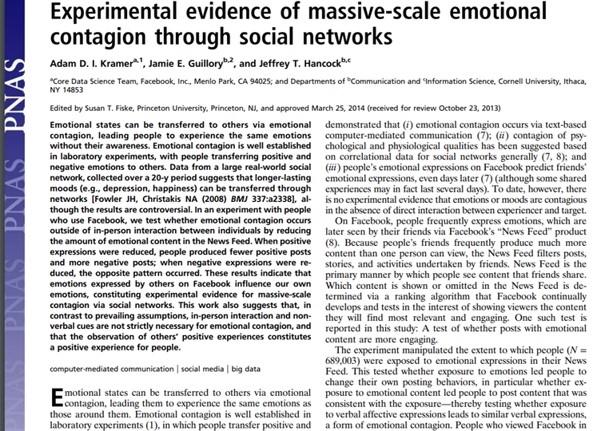

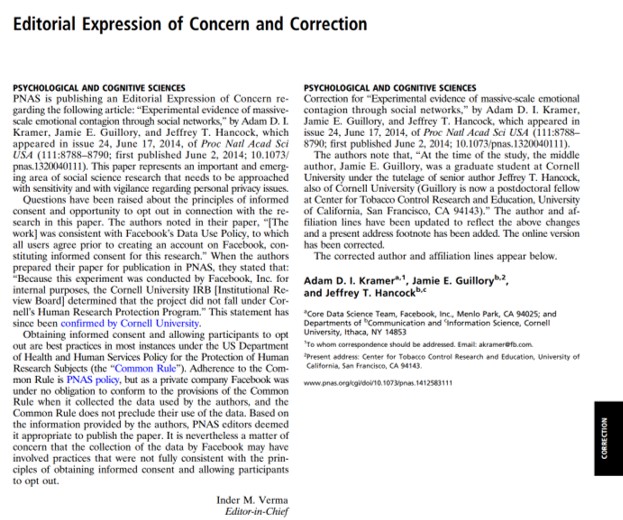

A paper back in 2014 set the stage for these kinds of ethical dilemmas. Kramer and colleagues’ paper simultaneously heralded the promise and danger within online research. While not the first paper to use ‘big data,’ it quickly drew mass-attention; the paper had huge amounts of data, advanced analyses, and big claims about how social media spreads emotions like hotcakes (Kramer, Guillory, Hancock, 2014). In short, they claimed they experimentally showed that emotions can be transferred through huge groups of people via Facebook posts. The paper was a prime example of the research potential of the modern online world.

However, the paper garnered far more attention for its questionable ethics. The authors manipulated the content presented to hundreds of thousands of Facebook profiles—without the consent of the participants and without their ability to remove themselves from the study—to experimentally manipulate users’ emotions. The lack of user consent and agency of their data violated the “Common Rule” for the protection of human subjects in science (Code of Federal Regulations), a rule that all federally funded projects and grants are required to abide by. However, the data they used did fall within Facebook’s Data Use Policy. Facebook, as a private entity who has not signed onto the “Common Rule”, is not obligated to follow those guidelines (Kramer et al., 2014). The paper showed how plausible it is with current technology to manipulate masses of people through online spaces without their knowledge or approval. In turn, it also shed greater light on the delicate divide between academic researchers and private companies.

A major ethical tension here is that the holders of user data are not beholden to the ethical standards of typical academic research. Modern online research challenges three core tenets of research ethics: privacy of information, informed consent, and anonymity (Townsend & Wallace, 2016). All three become tricky with the pervasiveness of online data: What is considered private data that is inappropriate to use? And can it be separated from public data for research? Have users been appropriately informed about the collection and usage of their data and can they reasonably refuse? Are users truly anonymous when we can collect data on personality, social networks, IP addresses, health biometrics, and GPS?

While weighty and complicated considerations, they are nonetheless required considerations for academics through institutional research boards and federal requirements for grant funding. Remember though, that most of this online data is collected and controlled by private companies, e.g. Facebook, Google, AT&T, etc. who don’t need to adhere to similar requirements (Wrzus & Mehl, 2015). These companies can push traditional ethical limits in research that otherwise bound academic research. This isn’t to say companies have no sense of research ethics. But they don’t have a similarly short leash like the academy. This also means that academics who want to use this online data are in an awkward position of having to juggle their own ethical standards with those of the data-controlling company’s for collaborative access. Some big events of the past few years have only piled on the stakes.

With Great Power…

As the most recent and largest-scale example to date, the Cambridge Analytica scandal drives at the heart of these ethical tensions in online personality research. In short, Cambridge Analytica scraped data from tens of millions of Facebook users and matched their personality profiles to voter profiles, allowing them to micro-target people for the purposes of mass sociopolitical influence (Cadwalladr & Graham-Harrison, 2018). Though its effectiveness is still unclear, Analytica’s purported ability to specifically target users via personality was tantalizing—enough for the Trump election team and Brexit campaign (among others) to pay millions for their services (Allen & Abbruzzese, 2018). The promise of Analytica is a powerful but concerning one, especially in an age of ‘fake news’ and divisive sociopolitical discourse. And though somewhat extreme, it runs parallel to the goals of companies who are trying to target their own consumer bases via personality. In other words, while Analytica’s actual effectiveness is questionable, its promise and real-world effects are quite real.

The major research ethics issue within the Analytica scandal was the way user privacy was so easily accessed and misused. To start, if you want to change people’s attitudes and opinions en masse, you need access to immense amounts of personal data from participants. And again, typically all participants must consent to their data being used and be able to remove themselves if they want. In Analytica’s case, they had about 320,000 users of a personality test on Facebook sign off on data usage (Cadwalladr, 2018). Analytica then scraped through the data of friends of those users too, on average about 160 friends each. This means that out of the over 50 million users affected by the Analytica campaign, less than 1% of them gave consent for their data to be used. And specifically, it was with the aim of manipulating users by personality types; a “psychological warfare tool” as whistleblower Christopher Wylie described it (pg 2, Cadwalladr, 2018). The Analytica scandal highlights the immense (at least perceived) power involved in this kind of online personality harvesting. It also shows how easily traditional ethical pillars can be brushed aside in a space that has high potential for extensive personal manipulation.

…Comes Great Responsibility

A lasting problem here is that ethical standards for digital research have been slow to adapt to the modern internet. And that doesn’t look to be changing anytime soon. To start, guidelines for designing online studies are old and sparse. The American Psychological Association, for example, has only three such documents, all from the early 2000s. With how quickly technology has evolved since then, such guidelines become less and less relevant (Kosinski, Matz, Gosling, Popov, Stillwell, 2015). In the academy at least, ethical frameworks for online research are gradually being understood as different from traditional social science research—requiring more dynamic, rather than prescriptive, standards to keep up with changing technology (Townsend & Wallace, 2016; Kosinski et al., 2015). Some have recommended even less traditional ethics codes, instead focusing on decision-making rules of thumb that can be more collaborative and context-specific (Markham, Tiidenberg, Herman, 2018). In any case, academic researchers have started to appreciate the widespread, potentially deep, implications of this kind of online research (Conway & O’Connor, 2016). However, these ethical discussions in the academy remain decidedly in-progress. Additionally, there is a concern that the current lack of clarity on online research ethics discourages industry researchers from using transparent science practices or pursuing their own ethical clearances (Kosinski et al., 2015). At the same time, research at these companies is performed increasingly by computer science researchers, rather than social scientists, who can be less familiar or concerned about the ethical and social implications involved with human-subjects research (Buchanan, Aycock, Dexter, Dittrich, Hvizdak, 2011).

The world of online research continues to be controversial, including concerns about privacy, anonymity, and consent among others (Kosinski et al., 2015; Conway & O’Connor, 2016; Townsend & Wallace, 2016; Wrzues & Mehl, 2015). Recent events like the Cambridge Analytica scandal highlight just how big the online personality field is as well as how much potential power and room for misuse there is. Consequently, the ethical tensions within online research have been increasingly laid bare to the scrutiny of the public eye. Big data online research will keep going. If anything, it has only just begun. But if online personality research is any indicator, the road ahead has both high potential and high stakes for all of us.

~~[–]~~

References

- Allen, J., & Abbruzzese, J. (2018, March 20). Cambridge Analytica’s effectiveness called into question despite alleged Facebook data harvesting. NBC News. Retrieved from https://www.nbcnews.com/politics/politics-news/cambridge-analytica-s-effectiveness-called-question-despite-alleged-facebook-data-n858256

- Boyd, & Pennebaker. (2017). Language-based personality: A new approach to personality in a digital world. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences, 18, 63-68.

- Buchanan,E., Aycock, S., Dittrich, D., Hvizdak, E. (2011). Computer science security research and human subjects: emerging considerations for research ethics boards. Journal of Empirical Research on Human Research Ethics: An International Journal, 6(2), 71-83. Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1525/jer.2011.6.2.71

- Cadwalladr, C. (2018, March 18). The Cambridge Analytica Files “I made Steve Bannon’s psychological warfare tool’: meet the data war whistleblower. The Guardian. Retrieved from http://davelevy.info/Downloads/cabridgeananalyticafiles%20-theguardian_20180318.pdf

- Cadwalladar, C., & Graham-Harrison, E. (2018, March 17). Revealed: 50 million Facebook profiles harvested for Cambridge Analytica in major data breach. The Guardian. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/news/2018/mar/17/cambridge-analytica-facebook-influence-us-election

- Code of Federal Regulations, Part 46–Protection of Human Subjects § 82 FR 7259, 7273 (2017).

- Conway, M., & O’Connor, D. (2016). Social media, big data, and mental health: current advances and ethical implications. Current Opinion in Psychology, 9, 77-82. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2016.01.004

- Farnadi, G., Sitaraman, G., Sushmita, S., Celli, F., Kosinski, M., Stillwell, D., . . . De Cock, M. (2016). Computational personality recognition in social media. User Modeling and User-adapted Interaction, 26(2-3), 109-142.

- Gosling, S., Augustine, A., Vazire, S., Holtzman, N., & Gaddis, S. (2011). Manifestations of Personality in Online Social Networks: Self-Reported Facebook-Related Behaviors and Observable Profile Information. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 14(9), 483-488.

- Han-Chung, H., Cheng, T.C.E., Huang, W.F, & Teng, C.I. (2018). Impact of online gamers’ personality traits on interdependence, network convergence, and continuance intention: perspective of social exchange theory. International Journal of Information Management, 38(1), 232-242. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2017.08.009

- Kern, M. L., Eichstaedt, J. C., Schwartz, H. A., Dziurzynski, L., Ungar, L. H., Stillwell, D. J., … Seligman, M. E. P. (2014). The Online Social Self: An Open Vocabulary Approach to Personality. Assessment, 21(2), 158–169. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191113514104

- Kosinski, M., Bachrach, Y., Kohli, P., Stillwell, D., & Graepel, T. (2014). Manifestations of user personality in website choice and behavior on online social networks. Machine Learning, 95(3), 357-380. doi: 10.1007/s10994-013-5415-y

- Kosinski, M., Matz, S., Gosling, S. D., Popov, V., Stillwell, D. (2015). Facebook as a research tool for the social sciences: Opportunities, challenges, ethical considerations, and practical guidelines. American Psychologist, 70(6), 543-556. doi: 10.1037/a0039210

- Kramer, A.D.I, Guillory, J. E., & Hancock, J.T. (2014). Experimental evidence of massive-scale emotional contagion through social networks. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 111(24), 8788-8790.

- Markham, A. N., Tiidenbergm K., & Herman, A. (2018). Ethics as methods: Doing ethics in the era of big data research—Introduction. Social Media + Society, 4(3). Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305118784502

- Marriott, T. C., & Buchanan, T. (2014). The true self online: Personality correlates of preference for self-expression online, and observer ratings of personality online and offline. Computers in Humab Behavior, 32, 171-177. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2013.11.014

- McCrae, R. R., & Costa, P. T. (1987). Validation of the five-factor model of personality across instruments and observers. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52(1), 81-90. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.52.1.81

- McCrae, R., & John, O. (1992). An Introduction to the Five‐Factor Model and Its Applications. Journal of Personality, 60(2), 175-215.

- McCrae, R. R., & Costa, P. T., Jr. (1990). Personality in adulthood. New York: Guilford.

- Souiden, N., Chtourou, S., & Korai, B. (2017). Consumer Attitudes toward Online Advertising: The Moderating Role of Personality. Journal of Promotion Management, 23(2), 207-227.

- Townsend, L., & Wallace, C. (2016). Social Media Research: A Guide to Ethics. Aberdeen: University of Aberdeen.

- Wrzus, C., & Mehl, M. R. (2015). Lab and/or field? Measuring personality processes and their social consequences. European Journal of Personality, 29(2), 250-271. https://doi-org.ezproxy.is.ed.ac.uk/10.1002/per.1986