When it comes to important life skills, reading is very near the top of the list. Few other skills are so universal and vital—so much so it’s easy to forget that reading is a skill at all. Literacy is the foundation upon which people acquire, build, and communicate all varieties of knowledge. Reading allows people to participate in parts of culture (e.g. literature), the workplace (e.g. emails), or even less obvious but important things like health and safety signs (e.g. allergy warnings). It makes sense then that illiteracy is a major contributor to inequality and directly costs the global economy more than $1 trillion every year (World Literacy Foundation, 2015). Yet despite the substantial direct and indirect costs, illiteracy is still a consistent problem, even in developed countries. About 20% of 15-year-olds in developed countries do not have baseline reading proficiency by the time they finish school, a trend that hasn’t improved since 2009 (Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, 2015).

I’ll be honest though, I’m no expert in the field of reading. But Professor Kathy Rastle is. She addresses a detrimental divide in reading education by explaining the science of why phonics, as opposed to whole-language approaches, should be the future of reading education. This blog post is a review of her recent paper (with Dr. Castles and Dr. Nation) and companion presentation at the University of Edinburgh. She’s a great speaker and researcher so if you’re interested I recommend taking a look at her work through the links above, but if you don’t want to dive too deep into the complexities, read on for my less-academic-ey summary of what’s going on in reading education.

What is This About “Reading Wars?”

People have been reading for a long time, so it makes sense to look at how people have been learning to read up to this point. In that time, we have seen both refinement and, more recently, turmoil. To start however, it’s worth remembering that people have not been blindly learning to read—reading itself has been studied for well over 100 years. Teaching people to read by linking sounds to letters directly, the base of what we now call phonics, goes back to at least the late 1500s. And those building blocks have shown to be sturdy enough to last through to the present. National education reviews in the U.S., U.K., and Australia all recommend following the phonics strategy. Researchers agree that phonics is the best strategy for teaching reading, however phonics is still untrusted by some laypeople and not universally adopted in education. This is partly down to the fact that education, on a local level, is affected by a teachers’ particular training and style. However, the emergence of a competing style, the whole-language approach, has really diverted progress.

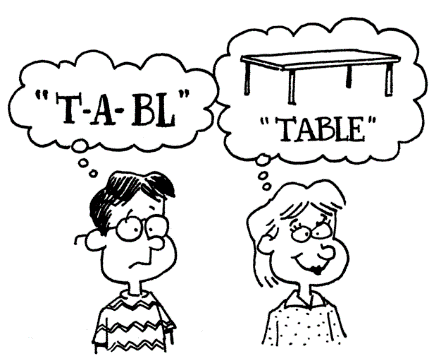

The idea of the whole-language approach is that words should be learned as paired with their environment. In other words, instead of learning how to sound out a word, students learn the whole sound of the word and use semantic and contextual cues to ‘associate’ the word. In other words, instead of learning how to sound out “t-ae-bl” from seeing the written word “table,” kids should learn how to recognize the whole word and sound “table” itself as directly indicative of the four-legged thing they eat breakfast on. This model has emerged from more constructivist philosophies of child-centered education that have become linked with liberal politics. This whole-language approach is actually quite intuitive for skilled readers. Indeed, it is how skilled readers tend to read themselves—skilled readers do not ‘sound out’ most things they read and they effortlessly draw meaning from words and objects in context. Reading is so effortless for skilled readers that this whole-language approach makes intuitive sense. However, Dr. Rastle reminds us that reading is technically hard and complicated to do and even more-so to learn. While skilled readers may not use phonics anymore because they do not need to, it is a mistake to teach reading to unskilled readers as if they can use a whole-language approach without first having the building blocks.

When in Doubt, Turn to the Scientists

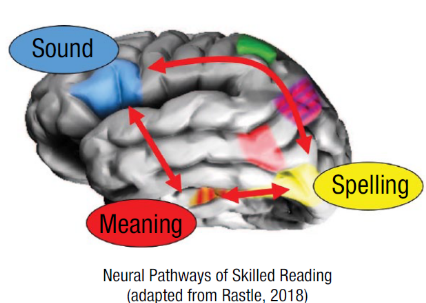

The overall reading challenge is linking three parts to each other: spelling, sound, and meaning. Children go into schooling with some experience with sound to spelling (phonic language) just from being around words spoken aloud in their daily lives. They also have experience with sound to meaning (oral language) from being around speaking people; this is the part that the whole-language approach focuses on. However, when it comes to that last connection, spelling to meaning, Dr. Rastle argues that phonics is the best approach to teach the tools to connect those dots. The key is getting people to link spelling to meaning—this is the core of reading fluency.

“Let’s start at the very beginning. A very good place to start”

Research has demonstrated that the best approach to promote this fluency is to start with the writing systems underlying the particular language. Dr. Rastle uses the example that, in English, “ABC” and “abc” spoken aloud sound the same but look very different on paper. There is a ‘code’ in the language that explains the differences and similarities between “ABC” and “abc.” The best way to map spellings to meanings from sound is by learning the codebook behind the language itself. The reason why phonics is the preferred way to learn reading is that phonics directly teaches that codebook. Take the words, cat/can/cut—it is easy to recognize the words on paper themselves (they each start with “c” and end with “t”) and they also have similar sounds. However, the meanings of these words have no pattern at all; in this case, the link between sound to spelling is relatively easy but the link between spelling to meaning is hard. A variety of experiments back up Dr. Rastle’s point that phonics better teaches how to handle that difficult spelling to meaning connection. Artificial language experiments where participants are taught to recognize words and sounds of a fake language learned the language better using phonics than whole-language. This is also evident from spelling-to-sound mapping experiments and specially designed storybooks for early leaners that have repetitious language (e.g. cat/can/cut). In both English and artificial languages, kids and adults taught with phonics can generalize (i.e. connect meaning and spelling) better than those using whole-language approaches. Dr. Rastle points out this is actually quite intuitive—people are better at learning systematically, i.e. from a writing system base, than from arbitrarily learning the meaning of words on the spot. Phonics focuses on giving readers the explicit rules to apply to those complex reading situations. Learn the sound to spelling link (phonics) first and then readers have the tools to break down the more complicated spelling to meaning link.

Mighty Morphin’: Shortcuts in Reading

Morphology refers to the understanding of morphemes, the base units of words. As described, cat/can/cut do not share meanings despite sounding so similar. However, they each have only one morpheme. For words that have more than one morpheme, learning all of their versions individually is ludicrously difficult. For example, clean/cleaned/unclean/cleaner/cleanliness all share the morpheme, “clean.” The meanings of these words are all different, but related. But rather than learning 5 words separately, phonics instead focuses on the parts which help teach common morphology; for example, learning that the morpheme “-ed” is a pair of letters generally reserved to something related to the past or how “un-“ tends to refer to the opposite of the original word. Dr. Rastle points out that a key aspect of this morphology knowledge is that it reduces the magnitude of learning this spelling-to-meaning link, difficult as is already, from learning 70,000+ words to (only) around 11,000. Phonics helps accentuate this morphology knowledge, helping to not only approach the spelling-to-meaning link, but also to reduce it to a far more manageable load. Indeed, children actually pick up on these kinds of morphemes before they start schooling and their use of these morphemes improves their spelling and reading ability in primary school. It therefore makes sense to tap into phonics education to encourage that development.

(Still) Hooked on Phonics

Phonics is intimately tied to the way the English alphabet is organized, it is cheap to implement, and it has nearly a century’s worth of literature and experience backing it up as the most effective way to teach reading. But Dr. Rastle points out more work needs to be done. Beyond just re-orienting reading education to phonics, additional work must be done about increasing text experience. Educators need to get more text in front of readers; in other words, early readers need to have more experience in front of, and using, words to develop better and long-lasting fluency. As Dr. Rastle puts it, phonics is the start of reading, but it is not the end of it. Learning to read takes a long time—decades even. But the overwhelming consensus in reading research is that phonics is the best way we know to teach reading. And it is likely the key to unlocking the best ways of teaching reading for all kinds of learners well into the future.

~~[—]~~

References

Castles, A., Rastle, K., & Nation, K. (2018). Ending the reading wars: Reading acquisition from novice to expert. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 19, 5–51. doi:10.1177/1529100618772271

Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, (2015). PISA 2015 Technical Report. Retrieved from http://www.oecd.org/pisa/data/2015-technical-report/

Rastle, K. (October 5, 2018). Ending the Reading Wars [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nisZ4og8xPk

World Literacy Foundation (2015). The Economic & Social Cost of Illiteracy: A snapshot of illiteracy in a global context. Retrieved from https://worldliteracyfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/WLF-FINAL-ECONOMIC-REPORT.pdf